by Kate Brown

Norton, 420 pp., $27.95

Midnight in Chernobyl: The Untold Story of the World’s Greatest Nuclear Disaster

by Adam Higginbotham

Simon and Schuster, 538 pp., $29.95

Chernobyl: The History of a Nuclear Catastrophe

by Serhii Plokhy

Basic Books, 404 pp., $32.00

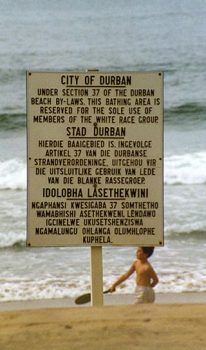

A worker measuring radiation after the explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in northern Ukraine, August 1986

On the night of April 25, 1986, during a planned maintenance shutdown at the Chernobyl power plant in northern Ukraine, one of the four reactors overheated and began to burn. As plant engineers scrambled to regain control of it, they thought for a moment that there had been an earthquake. In fact, a buildup of steam had propelled the two-hundred-ton concrete top of the reactor’s casing into the air, with masses of radioactive material following close behind when the core exploded. The plant workers had been assured again and again of the safety of the “peaceful atom,” and they couldn’t imagine that the reactor had exploded.

Firefighters rushed to the scene without special equipment or a clear understanding of the potential risks; they had not been trained to deal with a nuclear explosion, because such training would have involved acknowledging that an explosion was possible. They kicked at chunks of radioactive graphite that had fallen around the reactor, and their boots stuck to the melting, flammable bitumen that had been used, against all safety regulations, to coat the roofs of the plant’s buildings. Efforts to douse mysteriously fizzy, incandescent fires only made the conflagrations seethe with radioactive steam. (These fires probably contained uranium dioxide, one of the fuels used in the reactor.)

Feeling hot, the firefighters unbuttoned their jackets and took off their helmets. After less than thirty minutes they began to vomit, develop excruciating headaches, and feel faint and unbearably thirsty. One drank highly radioactive water from the plant’s cooling pond, burning his digestive tract. Over the next few hours, the exposed firefighters and plant workers swelled up, their skin turning the eerie purple of radiation burn. Later it would turn black and peel away. After evacuation and treatment in Moscow, many of these first responders died and were buried in nesting pairs of zinc caskets. Their graves were covered with cement tiles to block the radiation emanating from their corpses.

Moscow officials eventually realized that the reactor had exploded, and that there was an imminent risk of another, much larger explosion. More than thirty-six hours after the initial meltdown, Pripyat was evacuated. Columns of Kiev city buses had been sent to wait for evacuees on the outset.

Moscow officials eventually realized that the reactor had exploded, and that there was an imminent risk of another, much larger explosion. More than thirty-six hours after the initial meltdown, Pripyat was evacuated. Columns of Kiev city buses had been sent to wait for evacuees on the outskirts of the city, absorbing radiation while plans we tskirts of the city, absorbing radiation while plans were debated. These radioactive buses deposited their radioactive passengers in villages chosen to house the refugees, then returned to their regular routes in Kiev. Over the next two weeks, another 75,000 people were resettled from the thirty-kilometer area around Pripyat, which was to become known as the “Exclusion Zone,” and which remains almost uninhabited to this day.

General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev was informed that there had been an explosion and fire at the plant but that the reactor itself had not been seriously damaged. No one wanted to be the bearer of catastrophic news. When the occasional official raised the question of whether to warn civilians and evacuate the city of Pripyat, which had been built to house workers from the Chernobyl plant, he was admonished to wait for higher-ups to make a decision and for a committee to be formed. Panic and embarrassment were of greater concern than public safety. The KGB cut Pripyat’s intercity telephone lines and prevented residents from leaving, as part of the effort to keep news of the disaster from spreading. Some locals were savvy enough to try to leave on their own. But with no public warning, many didn’t take even the minimal precaution of staying indoors with the windows shut. One man was happily sunbathing the next morning, pleased by the speed with which he was tanning. He was soon in the hospital.

Moscow officials eventually realized that the reactor had exploded, and that there was an imminent risk of another, much larger explosion. More than thirty-six hours after the initial meltdown, Pripyat was evacuated. Columns of Kiev city buses had been sent to wait for evacuees on the outskirts of the city, absorbing radiation while plans we tskirts of the city, absorbing radiation while plans were debated. These radioactive buses deposited their radioactive passengers in villages chosen to house the refugees, then returned to their regular routes in Kiev. Over the next two weeks, another 75,000 people were resettled from the thirty-kilometer area around Pripyat, which was to become known as the “Exclusion Zone,” and which remains almost uninhabited to this day.

General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev was informed that there had been an explosion and fire at the plant but that the reactor itself had not been seriously damaged. No one wanted to be the bearer of catastrophic news. When the occasional official raised the question of whether to warn civilians and evacuate the city of Pripyat, which had been built to house workers from the Chernobyl plant, he was admonished to wait for higher-ups to make a decision and for a committee to be formed. Panic and embarrassment were of greater concern than public safety. The KGB cut Pripyat’s intercity telephone lines and prevented residents from leaving, as part of the effort to keep news of the disaster from spreading. Some locals were savvy enough to try to leave on their own. But with no public warning, many didn’t take even the minimal precaution of staying indoors with the windows shut. One man was happily sunbathing the next morning, pleased by the speed with which he was tanning. He was soon in the hospital.

The Soviet system began to marshal its vast human resources to “liquidate” the disaster. Many efforts to stop the fire in the reactor only made matters worse by triggering new reactions or creating toxic smoke, but doing nothing was not an option. Pilots, soldiers, firefighters, and scientists volunteered, exposing themselves to huge doses of radiation. (Many others fled from the scene.) They were rewarded with cash bonuses, cars, and apartments, and some were made “Hero of the Soviet Union” or “Hero of Ukraine,” but many became invalids or didn’t live to see their new homes. The radiation levels were so high that they made the electronics in robots fail, so “biorobots”—people in makeshift lead protective gear—did the work of clearing the area.

On April 28, a radioactive cloud reached Scandinavia. After attempts at denial, the Soviet government conceded that there had been an accident. Western journalists soon began reporting alarming estimates of Chernobyl casualties. To maintain the illusion that the accident was already under control, Moscow ordered Ukrainians to continue with the planned May Day parade in Kiev, about eighty miles away, thus exposing huge numbers of people—including many children—to radioactive fallout. Thanks to word of mouth and to their well-honed skill at reading between the lines of official declarations, however, Kiev residents were already fleeing. By early May, the exodus had grown so large that it became almost impossible to buy a plane, train, or bus ticket out of the city. Tens of thousands of residents left even before the official order to evacuate children was issued, far too late, on May 15. Thousands of people were treated for radiation exposure in Soviet hospitals by the end of the summer of 1986, but the Soviet press was allowed to report only on the hospitalizations of the Chernobyl firemen and plant operators.

A few decades later, it seemed to many that the world’s worst nuclear disaster had caused surprisingly little long-term damage. The official toll is now between thirty-one and fifty-four deaths from acute radiation poisoning (among plant workers and firefighters), doubled leukemia rates among those exposed to exceptionally high radiation levels during the disaster response, and several thousand cases of thyroid cancer—highly treatable, very rarely fatal—among children. Pripyat became a spooky tourist site. In the Exclusion Zone, one could soon see wolves, elk, lynx, brown bears, and birds of prey that had almost disappeared from the area before Chernobyl; some visitors described it as a kind of radioactive Eden, proof of nature’s resiliency. But striking differences in new books about Chernobyl by Kate Brown, Adam Higginbotham, and Serhii Plokhy show that there are still many ways to tell this story, and that the lessons of Chernobyl remain unresolved.Both Plokhy and Higginbotham devote their first sections to dramatic reconstructions of the disaster at the plant. Sketches of loving family life or youthful ambition introduce the central figures, making us queasy with dread. The two authors’ minute-by-minute descriptions of the reactor meltdown and its aftermath are as gripping as any thriller and employ similar techniques: the moments of horrified realization, the heroic races against time.

The prescient 1979 film The China Syndrome, about a barely averted disaster at a nuclear plant and its cover-up, is mentioned in both books. The movie’s title comes from a former Manhattan Project scientist’s hypothetical discussion of a reactor meltdown in North America causing fuel to burn its way through the globe to China. Though that specific scenario was clearly impossible, “China syndrome” became shorthand for anxieties about nuclear material burning through the foundations of the Chernobyl plant and entering the water table, the Dnieper River Basin, and then the Black Sea.Plokhy, a historian of Ukraine, provides a masterful account of how the USSR’s bureaucratic dysfunction, censorship, and impossible economic targets produced the disaster and hindered the response to it. Though the Soviets held a show trial to pin responsibility on three plant employees, Plokhy makes plain the absurdity of holding individuals accountable for what was clearly a systemic failure. But Chernobyl could have been worse. The Dnieper River Basin was not contaminated, there was no second explosion, and long-term damage was mercifully limited; eventually the fire burned itself out, and the reactor was covered with a 400,000-ton concrete “sarcophagus.”

The radioactive cloud may even have had a silver lining. Plokhy emphasizes Chernobyl’s role in the USSR’s final collapse and in the push for Ukrainian independence, as furious citizens worked to bring down the government responsible for the disaster, its cover-up, and the lethally inadequate response to it. For Plokhy, the greatest lesson of Chernobyl is the danger of authoritarianism. The secretive Soviet Union’s need to look invincible led it to conceal the many nuclear accidents that preceded Chernobyl, instead of using studies of them to improve safety. The memory of Stalin’s purges and the continuing threat of unjust punishment prevented plant workers and officials from reporting problems, while impossible Soviet quotas led plant employees to cut corners and ignore safety protocols. Once the reactor exploded, Soviet censorship kept citizens in the dark about the disaster, preventing them fromtaking measures to protect themselves.

But cover-ups and bureaucratic buck-passing don’t happen only in authoritarian governments. As her book’s title, Manual for Survival, suggests, Kate Brown is interested in the aftermath of Chernobyl, not the disaster itself. Her heroes are not first responders but brave citizen-scientists, independent-minded doctors and health officials, journalists, and activists who fought doggedly to uncover the truth about the long-term damage caused by Chernobyl. Her villains include not only the lying, negligent Soviet authorities, but also the Western governments and international agencies that, in her account, have worked for decades to downplay or actually conceal the human and ecological cost of nuclear war, nuclear tests, and nuclear accidents. Rather than attributing Chernobyl to authoritarianism, she points to similarities in the willingness of Soviets and capitalists to sacrifice the health of workers, the public, and the environment to production goals and geopolitical rivalries.

When the United States dropped atom bombs on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, the immediate effect was a huge single release of radiation. Radioactive fallout then drifted down from the sky, moving with the wind to distribute a smaller amount of radiation across a larger area. People who arrived in Hiroshima after the attack fell ill, including US soldiers helping to rebuild the city, and the Japanese press wrote about the longer-lasting effects of the “atomic poison.” This infuriated General Leslie Groves, head of the Manhattan Project, who could not countenance the possibility that the hugely expensive new weapon might be vilified and banned, as German mustard gas had been during and after World War I. Groves directed an effort to use censorship and propaganda to suppress information about the dangers of the radiation emitted by the atom bomb. The US did sponsor a “Life Span Study” of Japanese bomb survivors, which yielded valuable information. But it only started in 1950, too late for comprehensive results, and it only factored the initial blast, not fallout, into its estimates of radiation exposure. This meant that it excluded from consideration potentially radiation-induced health problems connected to lower doses of radiation, such as leukemia, thyroid cancer, diseases of the circulatory system, autoimmune disorders, eye diseases, and increase vulnerability.

In 1953 President Eisenhower announced “Atoms for Peace,” a program intended to use nuclear power for medicine and cheap electricity. Soon the cold war arms race was matched by the competitive construction of civilian nuclear reactors. The Soviet Union’s race to nuclear power, like its other industrialization drives, required the over-fulfillment of unrealistic quotas, often using substandard materials and undertrained personnel.

In 1953 President Eisenhower announced “Atoms for Peace,” a program intended to use nuclear power for medicine and cheap electricity. Soon the cold war arms race was matched by the competitive construction of civilian nuclear reactors. The Soviet Union’s race to nuclear power, like its other industrialization drives, required the over-fulfillment of unrealistic quotas, often using substandard materials and undertrained personnel.

In the 1950s the Soviets developed the High Power Channel Reactor (RBMK). They also developed a much safer alternative model, the Water-Water Energy Reactor (VVER), similar to the Pressurized Water Reactors used in the US. But the RBMK won out because it generated twice as much energy as the VVER, was cheaper to build and run, and produced plutonium that could potentially be used in weapons—though it emitted far more radiation and had not been fully tested before operation began. The four reactors at the Chernobyl plant, opened between 1977 and 1983, were all RBMKs. They generated vast quantities of electricity not only for civilian use but also for the nearby Duga Radar system, which had been built to detect nuclear missiles. In 1985 the shoddily constructed Chernobyl plant managed to overfill its production quotas, in part by reducing the amount of time allotted to repairs.

The Soviet Union had access only to the published results of the “Life Span Study.” But the rapid development of Soviet nuclear power, and the many accidents that accompanied it, provided extensive opportunities to examine the effects of radiation on the human body. By the time Dr. Angelina Guskova cared for Chernobyl responders, she had already treated more cases of radiation illness than anyone in the world. During years of work at a secret Siberian nuclear weapons installation where she was forbidden to ask her patients about the nature of their work, and thus about their radiation exposure, she learned to estimate radiation doses from victims’ symptoms, and she made substantial inroads in the treatment of radiation-related illness. She helped contribute to the Soviet definition of “chronic radiation syndrome,” which included malaise, sleep disorders, bleeding gums, and respiratory and digestive disorders. Guskova’s findings, like the many nuclear accidents that occurred in the Soviet Union in those years, were kept secret.

Chernobyl provided an opportunity to gather a vast body of knowledge about the effects of radiation exposure, but politics trumped science. In the 1990s, when studies of Chernobyl should have been in full swing, Americans and Europeans were suing their governments for exposing them to radioactivity through nuclear tests and accidents—hardly a situation in which Western governments would wish to publicize the many harms of long-term exposure. International agencies and diplomats worked to minimize reports of Chernobyl’s damage. Despite calls from scientists from many countries, there has never been a large-scale, long-term study of its aftermath. In 2011, when an earthquake caused an accident at the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant in Japan, there was still no firmly established understanding of the effects of chronic exposure to lower levels of radiation, or of the ways in which radioactive fallout continues to circulate years after a disaster.

With bountiful, devastating detail, Brown describes how scientists, doctors, and journalists—mainly in Ukraine and Belarus—went to great lengths and took substantial risks to collect information on the long-term effects of the Chernobyl explosion, which they believed to be extensive. When Soviet authorities were unwilling to accept their results or act on their warnings, these activists put their faith in foreign experts. They were sorely disappointed. In 1989, under public pressure, the Soviet Minister of Health requested that the World Health Organization send a delegation to the area around Chernobyl to determine what levels of radiation were safe for humans. The WHOselected a group of physicists who had already issued reassuring statements about the effects of the radiation spread by the accident. (Brown implies that this selection was connected to pressure from the world’s nuclear powers.) This group soon concluded that there was no association between Chernobyl fallout and the reported rise in noncancerous diseases such as circulatory or autoimmune disorders, and recommended a dramatic increase in the guideline for “safe” lifetime doses of radiation.

A 1990 assessment by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), meanwhile, was sabotaged by the KGB, which was so desperate to conceal sensitive information from foreigners that it stole a large registry of patient data kept on a single computer in Belarus. (It was never recovered.) According to Brown, the IAEA ended up producing inaccurate estimates of radiation exposure, in part because it grossly underestimated the use of contaminated local products by people living around the Zone—especially berries, mushrooms, and milk. The WHO and IAEA results hamstrung fundraising efforts for further Chernobyl studies, and for medical care and resettlement. Ukrainians and Belarusians were told that their health problems were caused by stress and “radiophobia” rather than by radiation itself.

One of the most alarming—though also eerily beautiful—aspects of Brown’s book is her description of the way radioactive material moves through organisms, ecosystems, and human society. Of the infamous May Day parade held in Kiev just after the explosion, Brown writes:

The newsreels of the May holiday did not record the actions of two and a half million lungs, inhaling and exhaling, working like a giant organic filter. Half of the radioactive substances Kyivans inhaled their bodies retained. Plants and trees in the lovely, tree-lined city scrubbed the air of ionizing radiation. When the leaves fell later that autumn, they needed to be treated as radioactive waste.

Radioactive fallout was distributed far beyond the Exclusion Zone, which was, after all, just a circle on a map. Clouds absorbed radiation and then moved with the wind. Red Army pilots were dispatched to seed clouds with silver iodide so that radioactive rain would fall over provincial Belarus rather than urban Russia. Belarusian villagers fell ill, as did the pilots. Livestock absorbed radiation in the immediate aftermath of the disaster by inhaling air and dust, and later by consuming contaminated grass. Cleaned villages were soon recontaminated by radioactive dust from surrounding areas, and buried material leaked radioactivity into the water table.

A reluctance to waste food and other basic goods helped keep the radioactive isotopes in circulation. (Radioactive isotopes are unstable atoms that release dangerous particles until they decay into stable atoms of different elements. Although scientists can estimate the half-life of radioactive isotopes, the process of decay at the level of individual atoms is random.) Contaminated wood and peat were burned for fuel in homes and factories, releasing more radioactivity into the air. The State Committee of Industrial Agriculture had 50,000 animals rounded up and slaughtered during the evacuation from the Zone, and their radioactive wool, hides, and meat sent to different cities for processing. Brown’s findings in a Kiev archive led her to Chernihiv, in northern Ukraine, where workers at a wool factory requested the same benefits received by those who had been at the site of the reactor explosion. The workers had held the Chernobyl wool in their hands and inhaled its fibers. Soon their noses started to bleed, and they became dizzy, nauseous, and fatigued. Their managers pushed them to fulfill their quotas anyway. The authorities eventually made some efforts to clean the factory, but they weren’t willing to bury the highly radioactive wool. Instead, it was piled near the factory’s loading dock, waiting for its isotopes to decay. Wool accumulated for over a year, continuing to emit radiation. Meanwhile, the cleaning efforts caused radiation to be released into the surrounding environment along with the rest of the factory’s waste.

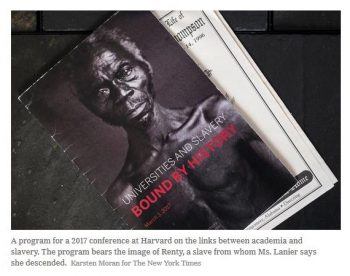

A mother holding a government document certifying that her daughter’s brain tumor was caused by radiation from the Chernobyl disaster, Zamishevo, Russia, 1999

Moscow agronomists explained how to make sausage with an “acceptable” amount of radioactive meat, and Chernobyl sausages were distributed across the USSR without special labeling. There were instructions on how to salvage contaminated milk, berries, eggs, beets, grain, spinach, potatoes, mushrooms, and tea—often by converting them into products with long shelf lives and simply storing them until the isotopes decayed. This misguided thriftiness was not a uniquely Soviet or authoritarian practice. Chernobyl fallout had contaminated much of Europe. When Italy rejected 300,000 tons of radioactive Greek wheat, Greece refused to take it back; the European Economic Community eventually agreed to buy the wheat, which was blended with clean grain and sent to Africa and East Germany in aid shipments.

The difficulty of the cleanup was increased by the fact that the Chernobyl plant had been built in a marshy area, the worst possible type of land for a nuclear disaster. Mineral-poor soil soaked up radioactive minerals, which were then absorbed by mineral-hungry plants. Meanwhile, seasonal floods spread contaminants into pastureland. Tim Mousseau and Anders Møller, biologists who have been studying Zone ecology since 2000, have found that microbes, worms, spiders, bees, and fruit flies still cannot function normally in the Zone, or that they exist in far lower numbers than they did before the meltdown. This means that leaves do not decay at the normal rate, pollination does not occur often enough to produce the fruit that feeds some birds, birds don’t spread the seeds for new plants, and so on.

Other researchers have issued a much sunnier picture of post-Chernobyl ecology, but Brown argues persuasively that they are grossly underestimating the scale of the damage, in part because they rely too heavily on simplistic measurements of radioactivity levels. Because radioactivity can move across so many environments and exposure to it can come in so many varieties, individual doses are hard to measure or even estimate, and a full understanding of radioactivity’s effects requires fine-grained observation at many levels over a long period. We don’t even fully understand the process of isotope decay. Biologists originally expected that the ecological half-life of cesium-137 would be only fifteen years; now researchers predict that it will take between 180 and 320 years for cesium-137 to disappear from the forests around Chernobyl, though they don’t yet know why.

Wild berry and mushroom picking is one of the few economic options for people in rural northern Ukraine. In her haunting conclusion, Brown describes a trip to the marshy forest a hundred kilometers from the Chernobyl plant. Pickers bring berries to a wholesaler who checks their radioactivity. The excessively radioactive berries are set aside for use in natural dyes, while the others are mixed with “cooler” berries until the assortment meets EU regulations. According to Brown, these regulations, like the American ones, are disturbingly lax. A nuclear security specialist told her that at the US–Canada border, a truck was stopped after officers detected a “radiating mass,” which they thought might be a dirty bomb. But it was only berries from Ukraine. The truck was allowed to pass.

Brown writes about anticipating outraged letters from nuclear scientists and plant workers, oncology clinic staff, and others whose jobs require exposure to radiation. She details her scrupulous efforts to check and double-check her data, consult with scientists from many fields, and account for factors that might skew results. I suspect that she may be accused of alarmism nonetheless.

But we should be alarmed about the ongoing consequences of nuclear leaks and the risk of new nuclear disasters. Higginbotham points out that the United States now operates a hundred nuclear power reactors, including the one at Three Mile Island that suffered a serious accident in 1979, just twelve days after the release of The China Syndrome. France generates 75 percent of its electricity from nuclear power plants, and China operates thirty-nine nuclear power plants and is building twenty more. Some people see nuclear power plants, which do not emit any carbon dioxide, as the most feasible way of limiting climate change, and new reactor models promise to be safer, more efficient, and less poisonous. But what if something goes wrong?

And what about nuclear waste? There are hundreds of nuclear waste sites in the US alone. In February the Environmental Protection Agency ordered the excavation of a landfill near St. Louis containing nuclear waste, dumped illegally, that dated back to the Manhattan Project. For years, an underground fire has been burning a few thousand feet from the dump. It took the federal government twenty-seven years to reach a decision about how to deal with this nuclear waste dump near a major metropolitan area, yet we fault the Soviet government for its inadequate response to a nuclear meltdown that unfolded in a matter of minutes. US failure to adequately address longstanding hazards—not to mention the slow-motion catastrophe of climate change—is yet another indication that poor disaster response is hardly unique to authoritarian regimes.

Then there is the renewed threat of nuclear war. One of Gorbachev’s biggest achievements was the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty, which eliminated US and Soviet land-based intermediate nuclear weapon systems. This February the US withdrew from the treaty, with President Trump citing Russian noncompliance. His administration recently called for the expansion of the US “low-yield” nuclear force, which includes weapons the size of those dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Analysts have pointed out that a greater diversity of nuclear weapons makes it harder for a target to know whether it is facing a limited or existential threat—and therefore raises the risk that the target will overreact.

Radiation has a special hold on our imagination: an invisible force out of science fiction, it can alter the very essence of our bodies, dissolve us from the inside out. But Manual for Survival asks a larger question about how humans will coexist with the ever-increasing quantities of toxins and pollutants that we introduce into our air, water, and soil. Brown’s careful mapping of the path isotopes take is highly relevant to other industrial toxins, and to plastic waste. When we put a substance into our environment, we have to understand that it will likely remain with us for a very long time, and that it may behave in ways we never anticipated. Chernobyl should not be seen as an isolated accident or as a unique disaster, Brown argues, but as an “exclamation point” that draws our attention to the new world we are creating.