Ottessa Moshfegh’s Otherworldly Fiction

The writer’s unusual discipline has come close to driving her crazy. The results have been both refined and depraved.

There was an unearthly quality to the atmosphere inside the Frieze New York art fair, like the air in a plane—still but pressurized, with an unsettling hum—when the fiction writer Ottessa Moshfegh visited to speak about her work one afternoon in May. “I hate this fair already,” she said when she walked in, handing her ticket to a very tall, very pale man dressed entirely in black lace. Almost immediately, she was lost in the labyrinth of works for sale: Takashi Murakami’s lurid blond plastic milkmaids with long legs and erect nipples; the words “any messages?” spelled out in neon tubing. It was like an enactment of the world inhabited by the protagonist of Moshfegh’s forthcoming novel, “My Year of Rest and Relaxation,” who works at a gallery in Chelsea, amid objects like a quarter-million-dollar “pair of toy monkeys made using human pubic hair,” with camera penises poking out from their fur. “Did I do this?” Moshfegh said, only half kidding. She sometimes gets the sense that she has the power to conjure reality through her writing.

There was an unearthly quality to the atmosphere inside the Frieze New York art fair, like the air in a plane—still but pressurized, with an unsettling hum—when the fiction writer Ottessa Moshfegh visited to speak about her work one afternoon in May. “I hate this fair already,” she said when she walked in, handing her ticket to a very tall, very pale man dressed entirely in black lace. Almost immediately, she was lost in the labyrinth of works for sale: Takashi Murakami’s lurid blond plastic milkmaids with long legs and erect nipples; the words “any messages?” spelled out in neon tubing. It was like an enactment of the world inhabited by the protagonist of Moshfegh’s forthcoming novel, “My Year of Rest and Relaxation,” who works at a gallery in Chelsea, amid objects like a quarter-million-dollar “pair of toy monkeys made using human pubic hair,” with camera penises poking out from their fur. “Did I do this?” Moshfegh said, only half kidding. She sometimes gets the sense that she has the power to conjure reality through her writing.

Though the details of Moshfegh’s books vary wildly, her work always seems to originate from a place that is not quite earth, where people breathe some other kind of air. Her novella “McGlue” is narrated by a drunken nineteenth-century sailor, with a cracked head, who isn’t sure if he has murdered a man he loves. “Eileen” is the story of a glum prison secretary, in the mid-nineteen-sixties, who is disgusted by her gin-sodden father and by her own sexuality (the “small, hard mounds” of her breasts, the “complex and nonsensical folds” of her genitals). Moshfegh’s characters tend to be amoral, frank, bleakly funny, very smart, and perverse in their motivations, in ways that destabilize the reader’s assumptions about what is ugly, what is desirable, what is permissible, and what is real. In her collection of short stories, “Homesick for Another World,” a little girl is convinced that a hole will open up in the earth and take her straight to paradise, if only she murders the right person. These characters share with their creator an intense sense of alienation, which she wrote about in a faux letter to Donald Trump: “Since age five, all of life has been like a farce, an absurd performance of a reality based on meaningless drivel, or a devastating experience of trauma and fatigue, deep with meaning, which has led me into such self-serious ness that I often wonder if I am completely insane. Can you relate at all?”

In the sprawling Frieze complex, Moshfegh found the tented room where she was meant to speak and got settled on a little stage in front of a few dozen people. She told them about the case of cat-scratch fever that she contracted in 2007, when she was working as an assistant and living in Bed-Stuy. A street cat leaped into her arms one night; when she brought him home and tried to wash the fleas off, he clawed her face. Hence “the illness that forced me out of New York City—which was a fucking godsend,” Moshfegh said. “Living in New York as a writer felt really claustrophobic; it seemed like everybody I knew had a similar ambition, and it was to be the standout literary voice of your generation, which I think is an insane ambition to begin with.” Moshfegh, who is thirty-seven, and looks like a skinny, Persian Anne Bancroft, was wearing black jeans and boots, an olive-green shirt, and a gold necklace that resembled an abstract spoon. Her peers back then believed, “Whatever it is that you’re going to do, you can’t just fit into the mold—you have to break the mold, blow people’s minds, do it perfectly, and then not care,” she continued. “Because if you care you’re not cool, and if you’re not cool you’re shit.”

Except for the not-caring part, Moshfegh had just offered a pretty accurate description of what she has accomplished. Her breakthrough novel, “Eileen,” won the PEN/Hemingway Award and was a finalist for the Man Booker Prize and the National Book Critics Circle Award. Scott Rudin bought the film rights. The Timessaid, of Moshfegh, “You feel she can do anything.” The Los Angeles Times declared her “unlike any other author (male, female, Iranian, American, etc.).” Part of what readers found so startling about the book was its female antihero, who is everything women are not supposed to be: “ugly, disgusting, unfit for the world,” as Eileen describes herself, but also angry, self-pitying, resentful. At the prison for wayward boys where she works, a girl comes in one day to confront her rapist, and Eileen snubs her. “I don’t know why I was so cold to her,” she muses. “I suppose I may have been envious. No one had ever tried to rape me, after all.”

Moshfegh created “Eileen” by being, according to the formula she had articulated, the antithesis of cool; she cares so deeply about her writing that it has come close to driving her crazy. For a long time, she was convinced that producing her best work required a monkish commitment to abstemiousness and isolation. “My life got really, really narrow,” she told me. “It’s not like I didn’t have adventurous experiences—my life had been interesting—but I was, like, No, no, no: not that. Just this. I was psychically tortured.”

In response to a question at Frieze on how she stays motivated, Moshfegh told a story about an ex-boyfriend. “He told me in the middle of an argument that being an artist was something that weak people indulge in, and I made him leave, because I guess what I feel is the opposite of that,” she said. “I think art is the thing that fixes culture, moment by moment. I don’t really feel a reason to exist unless I feel my life has a purpose, which is creating. So I feel—I’m not going to call it pressure—I feel I have a karmic role to play.” In her fictional letter to Trump, Moshfegh wrote, “Do you feel you’ve been chosen by God for a special task to accomplish here on Earth? I do.”

The blocks around Moshfegh’s apartment, just east of L.A.’s Little Armenia, are bedraggled: laundry hangs on a chain-link fence; the yards are yellow patches of dead grass on dust; water drips from an old air-conditioner in a window covered with tinfoil. But Moshfegh’s building, a two-story cluster of nineteen-twenties apartments, sits behind a gate, connected to the street by a walkway lined with roses and spindly purple skyflower. “I like it here,” she said in her living room, a clean, quiet space, which she had furnished with a burgundy couch, a Danish modern coffee table with a porcupine sculpture on top, and books lined up on the floor. She wore sandals and had her hair in a braid; all the windows were open, and the air smelled like rain. “It feels like a retreat.”

The unkempt neighborhood outside recalls the sort of place where many of her characters live. An alcoholic teacher in Moshfegh’s short story “Bettering Myself” begins her tale, “My classroom was on the first floor, next to the nuns’ lounge. I used their bathroom to puke in the mornings.” McGlue is forever “in the mud, drunk and tired and unwatched.” It is likewise the kind of setting where one might expect to find the characters of one of Moshfegh’s influences, Charles Bukowski, the late author of “All the Assholes in the World and Mine,” among dozens of other books, whom Time once called the “laureate of American lowlife.” Moshfegh told me that when she encountered his writing, in grad school, “I was, like, Oh, I can write about that, too.” The underbelly of human behavior and emotion could be literature, if it was approached with sufficient precision and passion. In “Eileen,” the narrator recounts the working of her bowels with relish: “With the laxatives, my movements were torrential, oceanic, as though all of my insides had melted and were now gushing out, a sludge that stank distinctly of chemicals and which, when it was all out, I half expected to breach the rim of the toilet bowl. In those cases I stood up to flush, dizzy and sweaty and cold, then lay down while the world seemed to revolve around me. Those were good times.” Moshfegh once told Vice, which published some of her early work, “My writing lets people scrape up against their own depravity, but at the same time it’s very refined . . . it’s like seeing Kate Moss take a shit.”

Moshfegh had positioned a small desk by the front window of her apartment, and on it she’d stuck a Post-it note, which read “Work hard the rest is a mystery.” She is not the sort of fiction writer who conducts methodical research and then labors to produce a faithful simulacrum of a time or a place. Moshfegh’s source material is her own imagination. “I think I could perfectly conjure 1910, the way it smelled and looked, but I can’t tell you the major world events that happened,” she said. The outside world is a place from which to snatch inspiration, details, feelings. “I just want to see the edge of the building, and then I want to go build it myself. That’s how I feel when I meet somebody: I just want this much.” She has lived in many places in her adult life, but she has isolated herself in almost all of them.

Since graduating from Barnard, in 2002, Moshfegh has moved every few years, which helps explain why her home is as spare as a grad student’s. She went first to Wuhan, China, where she taught English, worked at a punk bar, and lived in hundred-year-old cement group housing. “The walls were red—like really Communist red—and it was all grimy,” she said. “Maybe somebody would think it was ugly, but I thought it was really cool.” She had gone to China with a boyfriend, but they broke up in the middle of the trip. “It was a hundred and twenty degrees every day, and I had lost all my connections, and I felt like I was just wasting my life, dying. At some point, I stumbled on a picture of a dead person on the Internet, and I had an adrenaline rush. It made me feel that life was deeply valuable, and also there was an excitement about seeing something so private—sort of death porn.” She started Googling images of dead people every day. “I just got into the habit. It gave me energy.”

Moshfegh returned to New York City and, at the age of twenty-four, swore off romance. “I did not want to share, and I did not want to get attached, and I didn’t want to have to be responsible for anybody but myself,” she said. “Mostly, I wanted to focus on my work.” She got a job at the Overlook Press, and then another as an assistant to Jean Stein, a former editor at The Paris Review, who hosted literary salons in her penthouse, where Gore Vidal and Norman Mailer once got into a fistfight. They became close friends, and Stein encouraged her writing. But Moshfegh began experiencing strange symptoms. “It started off as intense exhaustion and disorientation. I would get on the subway and get off and I didn’t remember where I was going,” she said. “I would have phone calls with Jean and immediately forget what she had told me. And then I started having numbness in my hands, a twitch in my face, really bad headaches. I would wake up in the middle of the night drenched in sweat, my body clenching.” It took months before she was given a diagnosis of cat-scratch fever. “I could not think straight for a year.”

Hoping to escape the city, Moshfegh applied to the M.F.A. program at Brown, and was accepted. Her time there was productive, she said, but mostly because her scholarship allowed her to write without the distraction of a job. “You have a lot of people who aren’t good at writing yet telling you what to change about the way that you’re writing,” she said. “It’s a lot of mediocrity feeding on itself. So you better be radical, and you better hate everyone. Not that I did personally, but that I had to if I was going to protect the thing in me that I knew I wanted to grow.”

She had been focussed on short stories, but one day she came upon something in the library that shifted her course. “I read an article in a periodical from 1851, in Boston or Salem. It was just the name ‘McGlue’ as the title—already, I was, like, Yes, please. All it said was: ‘Mr. McGlue has been acquitted of the murder of Mr. Johnson in Zanzibar due to having been blackout drunk at the time of the murder and having sustained grave injury to the head from jumping off a train several months earlier.’ And that was it. That was the whole book. It was just handed to me.” What followed was an almost mystical experience of channelling—easy intellectually but difficult emotionally, because Moshfegh was never entirely sure that the spirit of McGlue wanted his story told. “I thought that maybe he was angry at me for betraying him,” she said. “It would give me the chills, and I would cry. There was some kind of resonance, like in a dream.” “McGlue” was selected as the winner of the Fence Modern Prize and published by Fence Books, in 2014.

McGlue is unreliable, intoxicated, and trapped—as are the narrators of Moshfegh’s other two novels. Eileen guzzles vermouth and feels enslaved by her abusive, alcoholic father; she spends much of the novel fantasizing about escaping from her frigid New England home town. The unnamed protagonist of “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” locks herself in her apartment and stays asleep as much as possible, with the help of Ambien, Benadryl, Nembutal, Xanax, and a fictional drug called Infermiterol. “A character facing discomfort or a problem is always going to try and feel differently,” Moshfegh said. “And substance and self-abuse and that kind of stuff always seems like ‘Well, that’s the first thing you would try.’ ” Drinking as an escape never worked for her, though. “I just knew that I was wasting my time and dumbing myself down to be in the company of dumb people because I was lonely,” she said. She turned instead to greater discipline.

After finishing at Brown, Moshfegh moved to Los Angeles, hoping to experience the freeing displacement of the West Coast. She went to Oakland next, after she was awarded a Stegner Fellowship at Stanford University. There she suffered. “I was losing it,” she said. “I wasn’t eating enough. I’d wake up at, like, five in the morning and have a banana, a cup of coffee, and then go to the boxing gym for three hours. I was working on ‘Eileen’ and the collection, and I was having zero fun, and it really started to take a toll on my psyche. It was a time when I was, like, I’m doing this. I’m tough. I’m tough. I’m tough.”

“She had become this kind of weapon,” Bill Clegg, who became Moshfegh’s agent after he read “McGlue,” said. “She seemed not to need anyone or anything. I understood that she had gone under and isolated herself completely in that book.” When it was finished, it was difficult to sell. “There was a lot of hand-wringing,” Clegg said. “People wanting something that was easier, and really being turned off by Eileen, like, ‘I really just don’t like her.’ ”

Eileen lives in a filthy house. She barely eats, but constantly drinks. (At one point, she falls asleep in her car, and wakes up next to a frozen pile of vomit.) She is so horrified by her genitals that she keeps them “swaddled like a baby in a diaper in thick cotton underpants and my mother’s old strangulating girdle.” Her sexuality is a source of shame and revulsion: “I wore lipstick not to be fashionable, but because my bare lips were the same color as my nipples.” But she burns with lust. She fantasizes obsessively about a prison guard named Randy, and watches transfixed as one of the boy prisoners masturbates in solitary confinement.

Despite all the praise that the book received when it was published, in 2015, Moshfegh is still upset by the intensity of people’s reaction to her character’s physicality. “They wanted me to somehow explain to them how I had the audacity to write a disgusting female character,” she said angrily. “It shocked me how much people wanted to talk about that.” Moshfegh intended readers to experience her protagonist as more self-loathing than repellent. “There was nothing really so wrong or terrible about my appearance,” Eileen says in the novel, when, as an old woman, she is looking back over her story. “I was young and fine, average, I guess. But at the time I thought I was the worst.”

“Denying her sexuality and swaddling her genitals—it is weird,” Moshfegh said. “But I guess I just feel like that is sort of what the message has been to me, or how I’ve interpreted messages: that my sexuality is actually really dangerous and disgusting.” Moshfegh developed severe scoliosis when she was nine, and, just as she started puberty, had to wear a brace for twenty-three hours of the day. “It was called the Boston brace,” she said. “It’s a hard plastic shell—thick—that goes around your entire torso and straps closed with industrial Velcro. I wore it for three years.” Like so many of her characters, she was imprisoned. “The message I was getting was: Your body is growing in a radically wrong direction.” Worst of all, the brace didn’t really work. Moshfegh showed me a recent X-ray of her spine that made me gasp: it curved like a snake.

One hot afternoon, Moshfegh was driving on Route 60 outside Chino, smoking out the window of her battered white BMW convertible, which she’d bought at a used-car lot a few months ago. She is an excellent driver—as precise behind the wheel as she is graceful when she walks, the result of years of physical therapy to compensate for her scoliosis. In conversation, she is definitive, clear, authoritative: in a theoretical discussion about playing a part in a totalitarian regime, she told me that she feared she’d be “uncomfortably high up.” She once told an interviewer, “I’m the most self-assured person I’ve ever met, very arrogant at times, sure. I can’t make a wrong move. I know what I’m doing.” When Moshfegh assesses her talent, she sounds less like a braggart than like a guileless child, announcing what she perceives to be inarguably accurate. “I have heard men much more frequently characterize their own work as superior,” Clegg told me. “I haven’t had that experience with women in the same way—perhaps because society has rewarded men for such assertions and women not so much.”

Moshfegh thinks that biology gives men and women a fundamentally different consciousness. “Men are more logic-centered,” she theorized. “They don’t have the same flexibility of thought, because they don’t have their mind transformed without their consent every month. And women have to see things in different dimensions.” She took a sip of Gatorade as she whizzed past an eighteen-wheeler. “The female genitalia—it’s so primordial, in a certain way,” she continued. “And I feel like, for us to get along and have codes of behavior, we can’t constantly be acknowledging that primordialness. We have adapted to a superficial environment, but I don’t know if the vagina has.”

Moshfegh never identifies herself as a feminist: it would require too much allegiance to a group. “It’s hard when people want to compare me to other women writers,” she said. “It’s like they’re only searching their mind database for women. Flannery O’Connor—I’m happy that they’re making that association, because she’s tops. But I don’t really feel like her. Someone once compared something I wrote to Nabokov, and I thought that was a huge compliment. I didn’t mind that.”

The heroine of “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” is similarly blunt about her assets. Unlike Eileen, she is “tall and thin and blond and pretty and young,” she says. “Even at my worst, I knew I still looked good.” But her looks are useless to her project, which is to sleep for a year, after which, she is sure, she’ll be reborn, healed, cleansed of her cynicism and indifference.

Although she is physically flawless, she is nonetheless an antihero. After she is fired from her job for napping in the supply closet, she defecates on the floor of the gallery. In relationships, she resists every stereotype of the female nurturer. From time to time, her best friend, Reva, whose mother is dying, comes by and disturbs her sleep:

She’d brag about all the fun things she was going to do over the weekend, complain that she’d gone off her most recent diet and had to do overtime at the gym to make up for it. And eventually, she’d cry about her mother. “I just can’t talk to her like I used to. I feel so sad. I feel so abandoned. I feel very, very alone.”

“We’re all alone, Reva,” I told her. It was true: I was, she was. This was the maximum comfort I could offer.

Reva is her only source of anything resembling intimacy. The nameless narrator has sex from time to time with an older guy, but it’s not exactly loving or even pleasurable: “I could count the number of times he’d gone down on me on one hand. When he’d tried, he had no idea what to do, but seemed overcome with his own generosity and passion, as though delaying getting his dick sucked was so obscene, so reckless, had required so much courage, he’d just blown his own mind.”

During her most intense period of solitary work, in California, Moshfegh committed herself to celibacy. Her sexuality “went away,” she told me. “I stopped menstruating. I was really determined: like this is a poison in my mind—lust—and seeing people as ‘What could that person be to me?’ It just seems so delusional. Looking for a boyfriend. Trying to look cute so that some guy’s gonna hit on me—not that that ever happened. Nobody ever hits on me, ever.”

Several years ago, a Vedic astrologer Moshfegh consults—“One of the most intelligent people I’ve ever met, probably one of the top five”—told her that love was inescapable. This struck her as a kind of threat. “The exact thing that the astrologer told me was ‘This is coming for you,’ ” she said. “ ‘If you move into a cabin in the middle of the woods, someone will come knock on your door.’ ”

In November, 2016, just before she published “Homesick for Another World,” a novelist named Luke Goebel wrote to Moshfegh from his cabin in the desert near Palm Springs, asking to interview her. She agreed. “He texted me when he got out of the car, and I came and opened the gate,” she recalled. “I saw him with his dog, and my precise thought was Oh, shit—here it is. Then I kind of surrendered.”

Goebel’s interview with Moshfegh, published on the Web site Fanzine, reads, in part:

Are you a witch? Are you in a cult? Are you an alien?

I hate cults.

Are you an other-dimensional being?

Yes, I am.

Do you want to talk about that?

There’s not much to say. I’m only conscious of what’s going on in this human form.

The interview lasted for twenty-seven days. “We just ate and fucked and slept and talked and talked,” Moshfegh said. On the wall in her living room is a framed copy of the first draft of Goebel’s introduction to the interview, which he typed up at the end of that monthlong meeting. (“I don’t know why he had a typewriter in his truck,” she said.) It begins, “These are the reasons I am now in love with Ottessa Moshfegh: She is arguably the most rapidly expanding powerful voice in American letters and when she speaks of what she believes in, has spent her life working to perfect, a righteous transgressive sensitive force speaks through her which is divinity in rebellion.” As I read it, she gave a little snort. “I wish he still felt that way about me,” she said, and laughed. After their long interview, Goebel went home to Oregon for Christmas, and while he was there his grandparents gave him a very large diamond ring they had, which he used to propose to Moshfegh when they saw each other again.

She wrote about their romance in a piece for the Wall Street Journal: “My man is the most beautiful man on Earth. ‘So handsome I couldn’t look,’ someone said when his back was turned. But I can look. I love to look.”

She also wrote in that piece about a different kind of love. “My little brother, whom I communicate with only telepathically because he is incarcerated, calls three times, and each time I miss his call. ‘An inmate at . . . ’ the messages begin. I tell my man in the desert about him, how he is the brutalized monster inside of my heart, that my heart has broken after each overdose, each jag of being missing, each arrest, each near-death experience. My baby brother.”

Moshfegh’s brother, Darius, died this past November. In her kitchen is a photograph of him as a toddler, asleep, clutching his toys. “We slept in the same bed until it became ridiculous,” she said. “I think I kind of believed that he was for me, because I had asked my parents for a brother. We were very, very close.”

After the funeral, while she was in Newton with her family, she used Darius’s car one day to run errands. In “Eileen,” which is set in the icy darkness of a New England winter, she describes such a day: “By afternoon, the sun had disappeared and everything froze all over again, building a glaze on the snow so thick at night it could hold the weight of a full-grown man.” In her brother’s car, under a pile of papers, Moshfegh happened upon one of his half-smoked Newport menthols. She lifted it to her lips and lit it. She has been smoking menthols ever since.

Moshfegh’s father, Farhoud, has lived all over the world. He was born in Arak, Iran, where his father had grown up in the walled Jewish ghetto and started selling cloth in the bazaar at the age of nine. (He went on to become a wealthy businessman and one of the biggest landowners in the country.) Farhoud left for Munich when he was nineteen, to study the violin, and then spent several years playing in a chamber orchestra in Taiwan. From there he went to Belgium, to study at the Royal Conservatory with the violinist André Gertler. He married a fellow-pupil from Zagreb, Croatia, who returned with him to Tehran—his favorite place of all. They were there for less than a year when the Islamic Revolution broke out. “I got a call that the Committee wanted me to come in and explain some things,” he recalled. Jews and intellectuals were already being executed; a week later, he left. All of the Moshfeghs immigrated to the United States and started over. Farhoud and his wife, Dubravka, settled in Newton, Massachusetts, where they played in orchestras, taught at the New England Conservatory, and brought up three children: Ottessa, Darius, and Sarvenaz, the eldest. They separated more than a decade ago but never divorced.

In April, Farhoud, who is seventy-six, packed a U-Haul with a grand piano, two hundred violins, ten cellos, and some furniture and paintings, and moved across the country, to a town called Mountain Center, an hour from Luke Goebel’s place in the desert. Sarvenaz and her two children are moving in with him soon. Ottessa has inadvertently led her family on a westward migration.

The latest Moshfegh outpost is a tidy house, surrounded by a pasture dotted with slender redwoods. Farhoud, who has a beard and straggly gray hair, was dressed in a muted beige Hawaiian shirt and cargo shorts when we visited on a recent afternoon. He was setting out a lunch of ghormeh sabzi, a Persian herb stew, which his sister had prepared and packed for him in empty yogurt containers when she visited recently from Las Vegas. He had cut some lilacs from the yard and put them on the table in a soup can. On the counter was a framed school picture of Darius.

Farhoud pointed out his new kitchen window at his neighbor’s house, in the distance. “This woman has seven horses and twelve goats,” he said. A mountain lion had eaten her dog.

“It’s weird to see all your stuff here,” Ottessa told him. In the living room was a giant painting of Paganini, wearing a look of alarming intensity. “It has a lot of depth,” she said. “I just feel like he might be trying to control my mind.”

“He was known to be very devilish when he played the violin,” Farhoud said. “His fingers were so flexible that he has written music that very few people can play. He died of syphilis.”

“Everybody died of syphilis,” his daughter replied.

Ottessa learned to read music before she could read words, and started playing piano when she was four. Throughout her childhood, she spent her Saturdays at the New England Conservatory. “I was supposed to practice four hours a day, especially if I was preparing for a competition or something. It was a constant responsibility and stress and goal,” she said. “I loved it, but it was also really painful, because, basically, you’re being presented with a work of ecstasy. Now you need to train yourself to play it fluently, and then maybe you can feel the ecstasy. But until you get there . . . ”

There was another painting on Farhoud’s wall of a clarinettist, which he bought at an antique store during a brief period when Ottessa studied clarinet as well as piano. “You were very good at it,” he recalled.

“I would have been very good on anything,” she said. “I don’t think I was especially good on the clarinet.”

“You were.”

“Well, if that’s true, then I had a really, really terrible teacher,” she said. “He is on my list—the list of men that should be snipped.”

Moshfegh studied music intently until her teens, when her allegiance slowly shifted to fiction. When she was fourteen, she wanted to go to a summer music program at Interlochen, in Michigan, but she missed the application deadline, so her mother signed her up for a creative-writing course there instead. “I was pretty tight-assed about being a pianist,” she recalled. “I remember being really pissed off.” She met her first mentor at Interlochen, a writer named Peter Markus, who taught poetry in Detroit public schools. “She was a student who didn’t need a teacher,” Markus told me. “I simply took her seriously.” Every day for the next three years, Moshfegh sent him her writing through the mail, and he returned it with his notes. “I can’t believe he did it,” she said. “I think my mom paid him a hundred bucks a month.” She stopped practicing piano when she decided not to go to music school. “But studying music and playing music, I think, was the foundation for the way that I look at writing,” she said. “Writing, to me, is more musical than I think it is literary a lot of the time—the way that a voice can sound and the way that it leads the reader in a sort of virtual reality, a journey through its own consciousness.”

If a voice is sufficiently compelling, the reader can forget the deranged circumstances that it is relating. The premise of “My Year of Rest and Relaxation”—that a woman sincerely believes she will become a better person if only she can hibernate—is insane, but it is easy to be lulled by the sound of the narrator’s thoughts: “As summer dwindled, my sleep got thin and empty, like a room with white walls and tepid air-conditioning. If I dreamt at all, I dreamt that I was lying in bed.”

Farhoud showed us the back room, where dozens of boxes were stacked, still waiting to be unpacked. He opened one to pull out some of Sarvanez’s paintings—large abstracts, which he unfolded on the floor. Ottessa pointed to one, a big, dark canvas with a kind of flaming tower in the corner, that she used to have in her apartment. “I just didn’t realize it was about 9/11,” she said. “That’s so creepy—it was hanging on my wall for years.” Initially, Moshfegh thought that “My Year of Rest and Relaxation,” which begins in June, 2000, would be primarily about September 11th. Moshfegh decided that Reva would work in the World Trade Center, and she researched the businesses that were housed there, up to a point. “I went so far as to contact Paul Bremer,” the terrorism expert who later administered the American occupation of Iraq. “He offered to talk to me, but I was too afraid.”

As sometimes happens to her, Moshfegh found life mirroring what she had written. “I was going through copy edits, reading the last page of Reva falling, when my friend called to tell me that Jean had jumped.” Jean Stein committed suicide in April, 2017, at the age of eighty-three, by jumping from her fifteenth-floor apartment on the Upper East Side. “My mom said Jean wanted people to know that she was strong—because the guts that must have taken, the height of her penthouse . . . ” Moshfegh told me that she thinks about Stein every day. “She was tough as shit.”

At night, the desert wind near Luke Goebel’s casita is so ferocious that it is hard to hear a voice. It sounds like the smashing of waves. “I call it the poor man’s ocean,” Goebel said one evening, when he got back from teaching his biweekly composition class at the University of California, Riverside. “It’s actually scary at times. It shakes the house.” Outside his windows the tamarisk trees looked like witches. Timothy Leary used to own a cabin nearby. Goebel’s neighbor is an iron sculptor named Chops. “But in here it looks like the home of a seventy-year-old woman,” Goebel said, accurately. He and Moshfegh had recently unloaded a shipping container of furniture from his grandparents, and now there were tasselled pillows, a Barcalounger, ceramic terriers on the coffee table, paintings of horse-drawn sleighs on the wall. “It’s such a ridiculous set—it’s a total sitcom,” Goebel said. “I think of it as an art piece.”

Like Moshfegh, Goebel lost his only brother, seven years ago. He wrote about that experience in his first novel, “Fourteen Stories, None of Them Are Yours.” The book, he told me, was “highly experimental, complicated. A lot of people can’t follow it—one out of ten, maybe.” Goebel has been working on his second novel for four years. “It’s a total bitch,” he said. “I had no idea how books worked when I met Tess—I just wrote how I wrote. I didn’t have the perspective to be, like, ‘How do you write a book that’s successful, that people actually want to read?’ I just wanted to do my own thing. Now I’m entertaining the question ‘What will a reader go for?’ ”

I pointed out that Moshfegh’s books are pretty weird. “My Year of Rest and Relaxation” is a page-turner about a woman who is almost always asleep. Eileen’s greatest joy is a case of explosive diarrhea.

“I don’t think ‘Eileen’ is a no-brainer,” Goebel said. “But I think when you put it into the context of how artists are also names, and names are also fetishized things, and when you’re winning the Plimpton Prize, and you’ve got a book that works on a level of nostalgia with a strong female narrator and she’s defying some of the mystery-of-womanhood shit that has been unveiled in the last five to ten years, and it’s written dynamite—then, yeah, I think you have a recipe for success.”

“To be completely fair,” Moshfegh interjected, “Luke hasn’t read ‘Eileen.’ ”

“I’ve read the beginning,” he said.

“Is it O.K. if I take a cigarette break?”

He laughed. “So what you’d like to do is just lob a grenade into the room and then walk out for a cigarette?”

Goebel, who is thirty-seven, tall, bearded, with floppy golden-brown hair, was sitting on the countertop in the kitchen; he looked as if he were in a movie from the late sixties. Moshfegh admired him briefly—“He looks good everywhere,” she said—and then returned to the matter of why he’d never finished her book. “You know what I think the real reason is? There’s a mystery that he’s trying to find out in his own book, and he doesn’t want to see how I did it, because maybe it will influence how he does it. I’m always arguing that it’s not the mainstream drivel that he thinks it is, and then he’s like—”

“Um, I never said it was mainstream drivel,” Goebel countered. “But I do think it’s accessible to the masses. Can I come outside, too?”

They went and sat on the patio together, where you could see the veins of snow on the mountaintops glowing blue under the moon. The couple talked about reconciling their opposing approaches to writing and to living—Moshfegh’s rigidity and Goebel’s heedlessness. “I never thought I’d own a home,” Goebel said. “I didn’t really think I was going to be thirty-six, thirty-seven. I lived a very reckless life style. I met you at the moment that my chaos had failed me. My creative process had led me to a novel I couldn’t finish because I needed more structure: I needed to be part of the regular world and put down some roots.”

“I was dealing with how to exist stepping off the path,” Moshfegh said, blowing smoke into the wind. “Then I met you and it was, like, Oh, this is a really smart move: that path was actually just going to loop back. I’d been walking on a wire, and he was—”

“Falling off a wire,” Goebel finished for her. “I drove off a cliff a year and a half ago. Sober. Doing sixty. I should have died.”

“Do you feel like your life is not doing that anymore?” Moshfegh asked. “I’m just wondering—in the last year and a half, like, is this still part of that?”

“No, you have absconded with all of the upheaval,” Goebel said. “All the chaos that used to be out there is now in our dynamic, and out there is just the quiet dark.”

This cracked her up. “We keep each other tethered,” she said. In the car, I’d asked what she found most compelling about her fiancé, and Moshfegh had told me, “He’s very innocent. I mean, that has its own challenges for him, personally, to be so open. He’s somebody who wants to connect a lot, and I don’t think I could be in a relationship with someone who wasn’t that connective.” Without his prodding, Moshfegh could easily slip back into the part of herself that is like her latest protagonist, a woman who relinquishes all the distractions and comforts of the outside world in order to reach her goal.

“What are you thinking?” she asked Goebel, looking at him intently.

“What am I actually right now thinking?” he said. “I am thinking that you’re a genius. That your writing is genius. You’re a genius.”

“Wow,” Moshfegh said. “Thank you. That’s not what I thought you were thinking.” She was quiet for a few moments and then said, “Is it a lie?” ♦

Ariel Levy joined

The New Yorker as a staff writer in 2008. She won a 2014 National Magazine Award for essays and criticism, and guest-edited “The Best American Essays 2015.” She is the author of “

Female Chauvinist Pigs.”

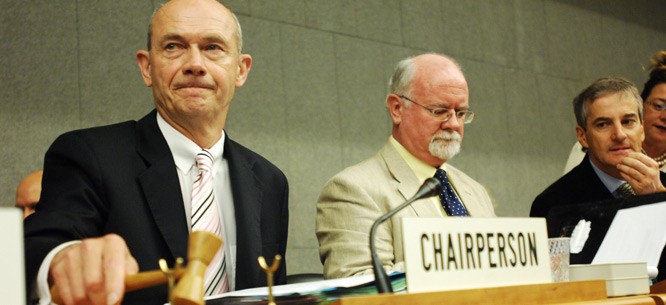

Pascal Lamy, former director-general of the World Trade Organization, leads a meeting of WTO ministers, July 2008 (© WTO / Flickr)

Pascal Lamy, former director-general of the World Trade Organization, leads a meeting of WTO ministers, July 2008 (© WTO / Flickr)